Myths & Misconceptions About Sustainable Architecture

Green design sounds aspirational, but it’s essential.

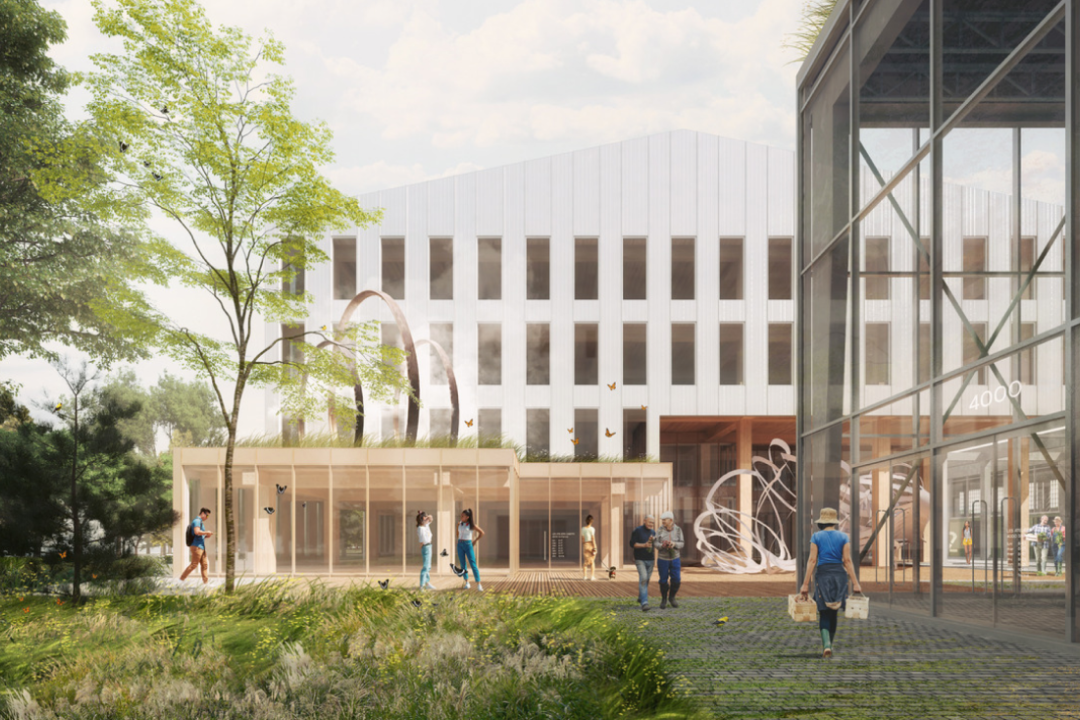

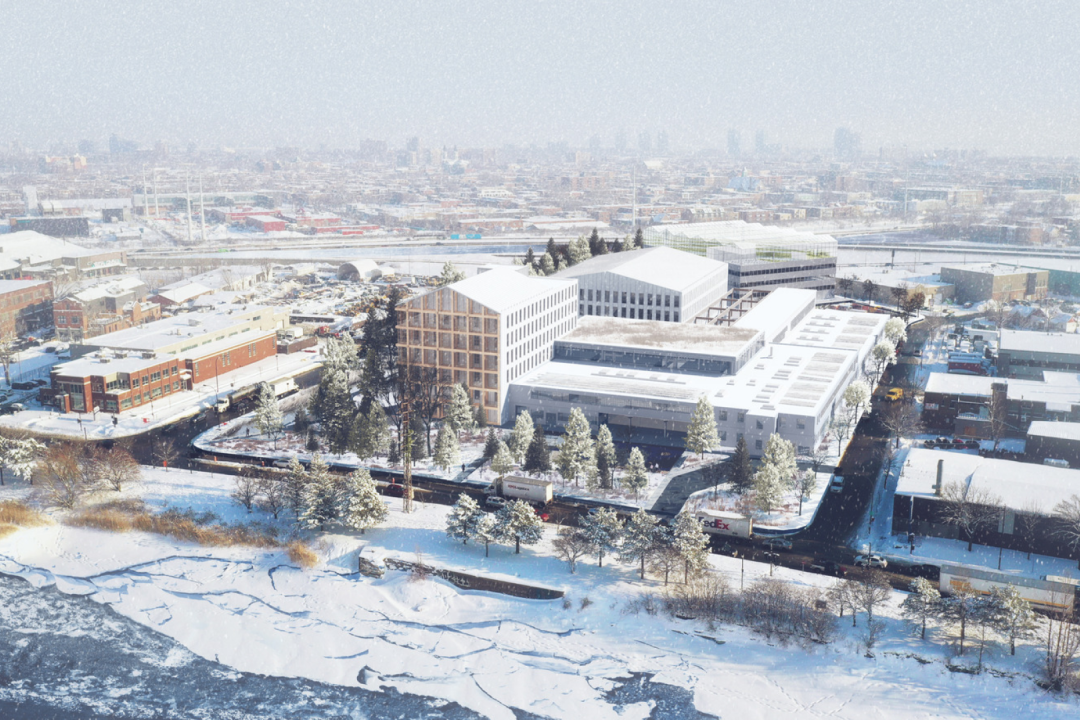

Image courtesy of Sid Lee Architecture

Our world is changing at a rapid pace and the places we live in need to change along with it. But while eco-friendly architecture is a “hot” topic of discussion, there are plenty of misconceptions that need to be set straight. Sid Lee Architecture architect Manuel R. Cisneros is ready to bust the myths that paint sustainable architecture as a “nice to have” rather than an urgent need.

From the very beginning of his professional journey, working in China in the early 2000s under a visionary mentor who focused on the materiality of architecture, Cisneros has spent his career considering the impact attached to architectural creation and finding ways to not just lessen the negative impacts of his buildings but also create positive impact.

Myth No. 1: It’s Not Practical

Designing buildings is certainly a creative act, but it’s also about problem-solving. What does that look like in practice? Cisneros is interested in designing “intelligent buildings” and that means considering things like water use, energy recycling, and waste management to create structures that truly work with the reality of our environment. He’s quick to point out that while architects are taught in school to “create beautiful buildings,” it isn’t pragmatic in today’s world where something that’s simply beautiful will likely not have lasting value.

Image courtesy of Sid Lee Architecture

Myth No. 2: Ecological Design Makes Things More Complicated

The key element that Cisneros considers in all of his projects is biodiversity. At Sid Lee Architecture, he isn’t simply an architect or a sustainability lead but the head of “environmental and regenerative strategies.” Instead of ignoring the environment around us, he says, “it’s about “creating a natural habitat, which is going to have buildings within it.” This approach may appear more complicated, but it actually helps society avoid future headaches.

For instance, knowing that rains will continue to be more intense in our changing climate, focusing on creating more permeable, “sponge cities” that can absorb water will save communities from dealing with the aftermath of continual flooding. Absorption also gives new life to plants and organisms that can provide ecosystem services such as better air quality, thermal comfort, production of nutrients, and carbon sequestration.

When it comes to successful sustainability in action, we have a true — easy to access — role model: Nature. In most buildings, water is treated as waste but it is our most important resource. Waste is a human creation and the more we take our cue from the natural world, the more we’ll be building for a thriving future.

Image courtesy of Sid Lee Architecture

Myth No. 3: The Architect’s Vision Is All That Matters

Smart, sustainable design should not be a solo effort. “You want to make the most sustainable project in the world? Become friends with your engineers,” Cisneros advises. Typically, engineers are not integrated into the design process from the beginning but doing so allows for a more creative output. An architect might design a building with a mechanical room on the roof by default but, in talking with an engineer, might learn that placing it in the center of a building allows for less tubing, making the roof available for energy and food production or use as a gathering space with great views.

Likewise, Cisneros is a proponent of engaging other subject matter experts who might not necessarily be consulted enough — such as biologists or landscape architects. “It’s not becoming an expert on everything; you have to become an expert in challenging your experts if you want to make real change in the future,” he says.

Image courtesy of Sid Lee Architecture

Myth No. 4: It’s Not Cost Effective

Developers and homeowners will both point to cost to avoid green builds, but Cisneros is emphatic that it makes no economic sense to build unsustainable buildings. Developers who continue to do things the way they’ve always done them will likely spend a fortune retrofitting their buildings due to changing regulations. Materials, like glass, that are currently common won’t be the materials of the future. Green design might seem more expensive, but it will also last twice as long, extending its value beyond monetary cost.

Value also means taking health and safety into consideration; embracing shared spaces can add environmental and cost benefits. A Sid Lee Architecture co-habitat project in Montreal exemplifies this: Although the apartments are smaller, the building has a greater number of common areas — large group kitchens and spaces for children, office work, and urban agriculture. Reducing the surface area of a unit allows it to be cheaper; increasing the amount of shared space and resources encourages community-based and multi-generational living.

“It’s not just about the affordability of the architecture but the affordability of the life attached to that architecture,” says Cisneros.

Image courtesy of Sid Lee Architecture

Myth No. 5: Green Additions Are Enough

What’s the first image that comes to mind when you imagine “sustainable architecture”? You might picture a home with solar panels or a roof garden. While it is important to consider these structural additions, Cisneros encourages thinking about the larger neighborhood or a city as an ecosystem. His systemic approach considers many more elements than a single structure.

“It's about what happens between the buildings, or between the building and the people and the natural elements of the site,” he says.

Designing multi-use buildings is key. Green urbanism is the name of the game. Creating clusters of services allows communities to become less reliant on cars (a top polluter and producer of CO2). The ultimate goal is to create neighborhoods that provide residents with everything that they need right outside their doors.

Sid Lee Architecture has twice participated in C40 Reinventing Cities competition, which challenges entrants to transform underutilized sites into sustainable, carbon-neutral developments. In their winning 2021 entry, Cisneros and his team turned a contaminated site in Montreal into a place community-gathering place, complete with artist studios, a bike shop to encourage a car-free lifestyle, and space for a food security company.

Images of Sid Lee Architecture's C40 Reinventing Cities entry "Village Urbain"

So, how can one be an effective architect for the present and the future? For Cisneros, it’s all about challenging the status quo and leading with empathy. Listening to the needs of the community and learning about the natural elements we must co-exist with are good starts.

“We have such a big responsibility when we create objects that are going to last hundreds of years and affect how people live, behave, and interact with each other,” he says. “The real goal of being more sustainable is being able to live together more easily, not only with other humans but also with all other species.”

Manuel R. Cisneros is an architect and Director, Environmental and Regenerative Strategies at Sid Lee Architecture.